Projection of future climatic extremes in Cuba under geoengineering scenarios

Main Article Content

Abstract

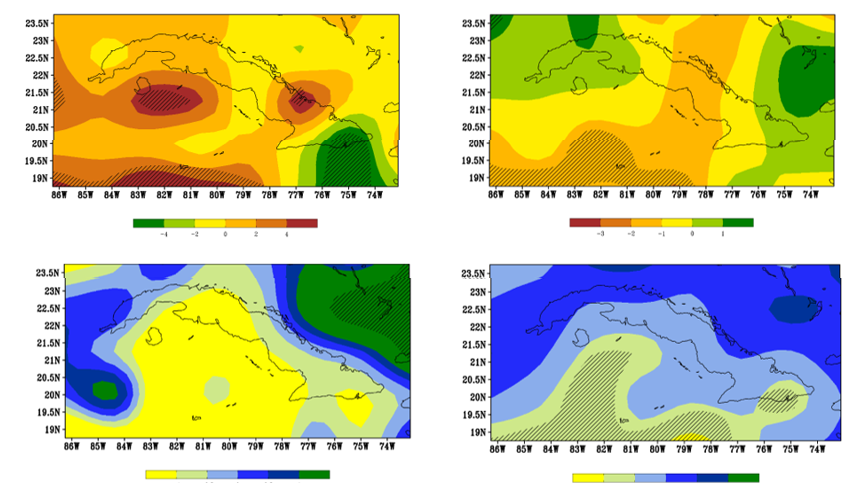

Faced with the evidence that confirms the warming of the climate system and the concerns about insufficient response measures to limit the increase in temperature global, Solar Radiation Management (SRM) has been considered as an additional action to mitigation and adaptation. Despite SRM being very controversial, an assessment of potential effects on the climate extremes could provide additional elements about its implications. In the present work, an analysis of the possible effects that the SRM would have is carried out by comparing the projections on the future climate of Cuba under SRM scenarios, with respect to a scenario of greenhouse gas emissions. The daily data of precipitation and maximum and minimum temperatures corresponding to the outputs of the HadGEM2-ES model for the RCP4.5 scenario and the two SRM G3 and G4 schemes were used. With this information, 10 indicators of climatic extremes in the future 2020-2070 were calculated and contrasted with respect to the reference period 1970-2000. The results show that the possible implementation of SRM with stratospheric aerosols could slightly improve the future scenario projected under RCP4.5 in relation to temperatures, by attenuating the increase or decrease of extremes related to the thermal regime. However, in the case of precipitation extremes, the estimated changes for the G3 and G4 scenarios are not significantly different from those projected under RCP4.5.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Those authors who have publications with this journal accept the following terms of the License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0):

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material

The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

The journal is not responsible for the opinions and concepts expressed in the works, they are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Editor, with the assistance of the Editorial Committee, reserves the right to suggest or request advisable or necessary modifications. They are accepted to publish original scientific papers, research results of interest that have not been published or sent to another journal for the same purpose.

The mention of trademarks of equipment, instruments or specific materials is for identification purposes, and there is no promotional commitment in relation to them, neither by the authors nor by the publisher.

References

Aswathy, N., Boucher, O., Quaas, M., Niemeier, U., Muri, H. Ø., & Quaas, J. (2014). Climate extremes in multi-model simulations of stratospheric aerosol and marine cloud brightening climate engineering. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 14, 32393-32425.

Boucher, O., Randall, D., Artaxo, P., Bretherton, C., Feingold, G., Forster, P., Kerminen, V.-M., Kondo, Y., Liao, H., Lohmann, U., Rasch, P, Satheesh, S.K, Sherwood, S, Stevens, B, & Zhang, X.Y. (2013). Clouds and aerosols. En Stocker, T.F, Qin, D, Plattner, G. K, Tignor, M, Allen, S.K, Boschung, J, Nauels, A, Xia, Y, Bex, V, & Midgley, P.M (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 571-657). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.016,

Budyko, M. I. (1977). On present‐day climatic changes. Tellus, 29(3), 193-204.

Burgos, Y., & González, I. T. (2012). Análisis de indicadores de extremos climáticos en la isla de Cuba. Revista de Climatología, 12, 81-91.

Campbell, J. D., Taylor, M. A., Stephenson, T. S., Watson, R. A., & Whyte, F. S. (2011). Future climate of the Caribbean from a regional climate model. International Journal of Climatology, 31(12), 1866-1878.

Centella, A., & Bezanilla, A. (2019). High spatial resolution climate change scenarios for Belize (p. 37) [Informe inédito de consultoría en apoyo a la Cuarta Comunicación Nacional de Belice sobre el cambio climático]. Instituto de Meteorología de Cuba.

Clarke, L. A., Taylor, M. A., Centella-Artola, A., Williams, M. S. M., Campbell, J. D., Bezanilla-Morlot, A., & Stephenson, T. S. (2021). The Caribbean and 1.5° C: Is SRM an Option? Atmosphere, 12(3), 367.

Collins, W., Bellouin, N., Doutriaux-Boucher, M., Gedney, N., Halloran, P., Hinton, T., Hughes, J., Jones, C., Joshi, M., & Liddicoat, S. (2011). Development and evaluation of an Earth-System model-HadGEM2. Geoscientific Model Development, 4(4), 1051-1075. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-4-1051-2011.

Crutzen, P. J. (2006). Albedo enhancement by stratospheric sulfur injections: A contribution to resolve a policy dilemma? Climatic change, 77(3-4), 211.

Curry, C. L., Sillmann, J., Bronaugh, D., Alterskjaer, K., Cole, J. N., Ji, D., Kravitz, B., Kristjansson, J. E., Moore, J. C., & Muri, H. (2014). A multimodel examination of climate extremes in an idealized geoengineering experiment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 119(7), 3900-3923.

Gil, L., González, I., Hernández, D., & Alvarez, M. (2020). Extremos climáticos de temperatura y su relación con patrones atmosféricos de teleconexión durante el invierno. Revista Cubana de Meteorología, 26(4).

González García, I. T., Barcia Sardiñas, S., & Hernández González, D. (2017). Comportamiento de Indicadores de extremos climáticos en la Isla de la Juventud. Revista Cubana de Meteorología, 23(2), 217-225.

González, I. (2004). Evaluación de índices climáticos extremos derivados de datos diarios [Tesis de Maestría, Instituto Superior de Tecnología y Ciencias Aplicadas]. https://repositorio.geotech.cu/jspui/bitstream/1234/1644

González, I. T., Barcia, S., Hernández, D., Paz, L. R., Gil, L., & Sánchez, F. (2019). Indicadores Climáticos Extremos en Cuba (p. 35) [Informe inédito para Proyecto Tercera Comunicación Nacional de Cambio Climático en Cub]. Instituto de Meteorología de Cuba.

Ji, D., Fang, S., Curry, C. L., Kashimura, H., Watanabe, S., Cole, J. N., Lenton, A., Muri, H., Kravitz, B., & Moore, J. C. (2018). Extreme temperature and precipitation response to solar dimming and stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 18(14), 10133-10156.

Klein Tank, A, Zwiers, F, & Zhang, X. (2009). Guidelines on analysis of extremes in a changing climate in support of informed decisions for adaptation (Guía WCDMP No.72-WMO/TD-No. 1500). WMO.

Kravitz, B., Robock, A., Boucher, O., Schmidt, H., Taylor, K. E., Stenchikov, G., & Schulz, M. (2011). The geoengineering model intercomparison project (GeoMIP). Atmospheric Science Letters, 12(2), 162-167.

McLean, N. M., Stephenson, T. S., Taylor, M. A., & Campbell, J. D. (2015). Characterization of future Caribbean rainfall and temperature extremes across rainfall zones. Advances in Meteorology, 2015.

Mycoo, M. A. (2018). Beyond 1.5 C: vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies for Caribbean Small Island developing states. Regional environmental change, 18(8), 2341-2353.

Neelin, J. D., Münnich, M., Su, H., Meyerson, J. E., & Holloway, C. E. (2006). Tropical drying trends in global warming models and observations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(16), 6110-6115.

Nurse, L. A., McLean, R. F., Agard, J., Briguglio, L. P., Duvat-Magnan, V., Pelesikoti, N., Tompkins, E., & Webb, A. (2014). Small islands. En Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, T.E, Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L, Estrada, Y.O, Genova, R.C, Kissel, E.S, Levy, A.N, MacCracken, S, Mastrandrea, P.R, & White, L.L (Eds.), Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects (pp. 1613-1654). Cambridge University Press.

Peterson, T. C., Taylor, M. A., Demeritte, R., Duncombe, D. L., Burton, S., Thompson, F., Porter, A., Mercedes, M., Villegas, E., & Semexant Fils, R. (2002). Recent changes in climate extremes in the Caribbean region. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 107(D21), ACL-16.

Robinson, S. (2018). Adapting to climate change at the national level in Caribbean small island developing states. Island Studies Journal, 13(1).

Ryu, J.-H., & Hayhoe, K. (2014). Understanding the sources of Caribbean precipitation biases in CMIP3 and CMIP5 simulations. Climate dynamics, 42(11), 3233-3252.

Serrano, S., Ruiz, J. C., & Bersosa, F. (2017). Heavy rainfall and temperature proyections in a climate change scenario over Quito, Ecuador. LA GRANJA. Revista de Ciencias de la Vida, 25(1), 16-32.

Stephenson, T. S., Vincent, L. A., Allen, T., Van Meerbeeck, C. J., McLean, N., Peterson, T. C., Taylor, M. A., Aaron‐Morrison, A. P., Auguste, T., & Bernard, D. (2014). Changes in extreme temperature and precipitation in the Caribbean region, 1961-2010. International Journal of Climatology, 34(9), 2957-2971.

Taylor, M. A., Clarke, L. A., Centella, A., Bezanilla, A., Stephenson, T. S., Jones, J. J., Campbell, J. D., Vichot, A., & Charlery, J. (2018). Future Caribbean climates in a world of rising temperatures: The 1.5 vs 2.0 dilemma. Journal of Climate, 31(7), 2907-2926.

Zhang, X., Yang, F., & Santos, J. L. (2004). RClimDex (1.0). Manual del usuario. Climate Research Branch Environment Canada. Versión en español: Santos, JL CIIFEN.