Anomaly of the El Niño Costero 2017 and its influence on the southern summer rainfall in Bolivia

Main Article Content

Abstract

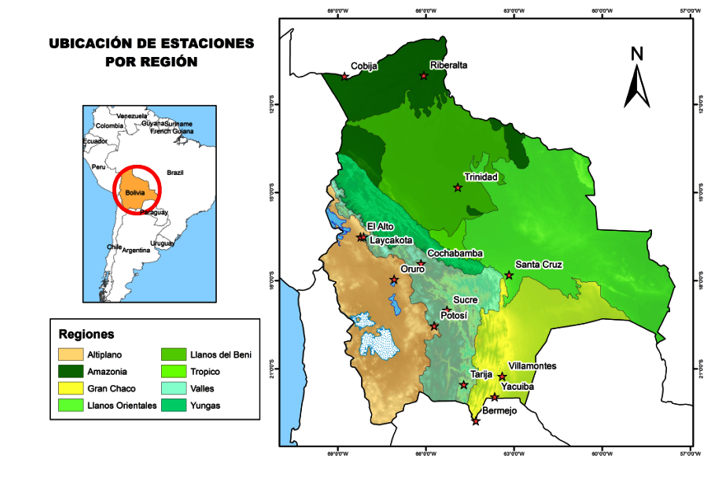

In the summer of 2017 appeared El Niño Costero, an atmospheric phenomenon which has influenced either in the absence of rainfalls or in floods in Colombia, Ecuador, Perú, and Bolivia causing the loss of human lifes and economic resources. The main issue was which atmospheric parameters have influence to get such absence and excess of rainfalls in different regions around Bolivia during El Niño Costero in 2017? To have a better understanding of the natural threats in South America it has been used a rainfall record, sea surface temperature maps, animations, images and a reanalysis of NCEP/NCAR for the last 30 years from 14 weather stations located in 5 different regions of Bolivia. The whole data and information has been verified applying measurements of descriptive statistics and qualitative comparisons. As a conclusion: The origin of El Niño Costero’s waters originated in the Chiriquí’s gulf (Panama) and in Coronado Bay (Costa Rica). Moreover, on January the subtropical Jet stream has contributed to the displacement of the SO of Bolivian’s high as a result there have not been any rainfalls for 26 days in the Andean region. On the other hand, in the eastern plains the maximum precipitation recorded 152,2 mm in 24 hours causing a large number of floods due to the intensification and interrelation of the high, medium and low level’s systems. Another reason to point out is the influence of the semi-permanents Pacific high and the Atlantic high have caused intense convective and frontal rainfalls.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Those authors who have publications with this journal accept the following terms of the License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0):

You are free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material

The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

The journal is not responsible for the opinions and concepts expressed in the works, they are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Editor, with the assistance of the Editorial Committee, reserves the right to suggest or request advisable or necessary modifications. They are accepted to publish original scientific papers, research results of interest that have not been published or sent to another journal for the same purpose.

The mention of trademarks of equipment, instruments or specific materials is for identification purposes, and there is no promotional commitment in relation to them, neither by the authors nor by the publisher.

References

Andressen, R., Monasterio, M., & Terceros, L. F. (2007). Regímenes climáticos del altiplano sur de Bolivia: Una región afectada por la desertificación. Revista geográfica venezolana, 48(1), 11-32.

Camilloni, I., Barros, V., Moreiras, S., Poveda, G., & Brasil, J. T. (2020). Inundaciones y sequías. En Adaptación frente a los riesgos del cambio climático en los países iberoamericanos (pp. 391-417). McGraw-Hill. http://rioccadapt.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/10_Cap_10_CambioClimatico.pdf

Castro, L. M., & Carvajal, Y. (2010). Análisis de tendencia y homogeneidad de series climatológicas. Ingeniería de Recursos Naturales y del Ambiente, 9, 15-25.

CONPES. (2017). Plan para la Reconstrucción del Municipio de Mocoa, 2017-2022 (p. 92) [Plan de Gobierno]. Departamento Nacional de Planeación de la República de Colombia. http://www.camara.gov.co

Días, J., & Tomaziello, A. (2008). Vórtices Ciclônicos de Altos Níveis de origem tropical e extratropical sobre o Brasil: Análise sinótica. XV Congresso Brasileiro de Meteorologia e XV Congresso Brasileiro de Meteorologia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271910329_Vortices_Ciclonicos_de_Altos_Niveis_de_origem_tropical_e_extratropical_sobre_o_Brasil_analise_sinotica

ENFEN. (2012). Definición operacional de los eventos El Niño y La Niña y sus magnitudes en la costa del Perú (p. 3) [Nota Técnica]. Estudio Nacional del fenómeno “El Niño”. http://www. imarpe.pe/imarpe/archivos/informes/imarpe_inftco_nota_tecnico_abril2012.pdf

ENFEN. (2017). El Niño Costero 2017 (Informe Técnico Extraordinario N°001-2017; p. 30). Estudio Nacional del fenómeno “El Niño”. http://enfen.gob.pe/download/informe-tecnico-el-nino-costero-2017

Enfield, D. B. (1989). El Niño, past and present. Reviews of geophysics, 27(1), 159-187.

Espinoza, J. C., Garreaud, R., Poveda, G., Arias, P. A., Molina-Carpio, J., Masiokas, M., Viale, M., & Scaff, L. (2020). Hydroclimate of the Andes Part I: main climatic features. Frontiers in Earth Science, 8, 64.

Galdos, A. W., & Mosquera, K. A. (2018). Observando el océano durante el evento El Niño costero 2017. Boletín Técnico, 5(1), 2. https://repositorio.igp.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12816/4665

Garreaud, R. D. (2018). A plausible atmospheric trigger for the 2017 coastal El Niño. International Journal of Climatology, 38, 1296-1302.

Hauser, A. (2000). Remociones en masa en Chile (p. 89) [Informe Nacional]. Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería. https://portalgeo.sernageomin.cl/Informes_PDF_Nac/RM-2000-09.pdf

Hogancamp, K. J. (2017). Characterizing South American Mesoscale Convective Complexes Using Isotope Hydrology [Masters Theses, Department of Geography and Geology Western Kentucky University]. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1937

Huamani, C., & Vargas, P. (2017). Azúcar y avenidas en el valle de Chicama: El impacto del fenómeno El Niño de 1925-1926 en la Hacienda Roma. Revista DiaCrónica, Año VI(4), 63-73. https://revistadiacronica.wordpress.com/2017/03/09/azucar-y-avenidas-en-el-valle-de-chicama-el-impacto-del-fenomeno-el-nino-de-1925-1926-en-la-hacienda-roma/

Kalnay, E., Kanamitsu, M., Kistler, R., Collins, W., Deaven, D., Gandin, Lev, Iredell, Mark, Saha, Suranjana, White, Glenn, Woollen, John, & others. (1996). The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project. Bulletin of the American meteorological Society, 77(3), 437-472. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO;2

Le Goulven, P., Alemán, M., & Osorno, I. (1988). Homogeneización y regionalización pluviométrica por el método del vector regional. 95-118. https://www.researchgate.net/publication

Lima, E. (2010). Influência dos fenômenos acoplados océano atmósfera sobre os vórtices ciclônicos de altos níveis observados no Nordeste do Brasil [Tesis de Doctorado en Meteorología, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, UFCG]. http://lattes.cnpq.br/6245822021636784

Mamani, H. (2012). Análisis de sistemas y complejos convectivos [Bachelor Thesis, Facultad Técnica, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés]. https://repositorio.umsa.bo/xmlui/handle/123456789/13886

Marapi, R. (2015). Un << Nino>> de invierno que puede convertirse en un fuerte << Nino>> de verano: Entrevista a Pablo Lagos. La revista agraria, 177.

Martínez, R., Rivadeneira, A., & Nieto, J. (2011). Guía de buenas prácticas para la predicción estacional en Latinoamérica (p. 55). Centro internacional para la investigación del fenómeno El Niño-CIIFEN. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256980652

Martínez, R., Zambrano, E., Nieto, J. J., Hernández, J., & Costa, F. (2017). Evolución, vulnerabilidad e impactos económicos y sociales de El Niño 2015-2016 en América Latina. Investigaciones Geográficas, 68, 65-78.

Miranda, G., Campero, S., & Chura, O. (2017). Caracterización del clima del valle de la ciudad de La Paz. En M. I. Moya, R. I. Meneses, & J. Sarmiento (Eds.), Historia Natural del Valle de La Paz (3ra ed., pp. 40-61). Museo Nacional de Historia Natural.

OMM. (2018). Guía de prácticas climatológicas (Edición de 2018). OMM.

Ormaza, F. I., & Cedeño, J. M. (2018). El Niño Costero 2017 in Niño 1+2 or simply: The Carnival Warming event? 4th International Symposium on the Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Oceans (ECCWO). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325815892

Pabón, J. D., & Montealegre, J. E. (2017). Los fenómenos de El Niño y de La Niña, su efecto climático e impactos socioeconómicos. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales.

Puertas, O. L., Carvajal, Y., & Quintero, M. (2011). Estudio de tendencias de la precipitación mensual en la cuenca alta-media del río Cauca, Colombia. Dyna, 78(169), 112-120.

Ramírez, I. J., & Briones, F. (2017). Understanding the El Niño Costero of 2017: The Definition Problem and Challenges of Climate Forecasting and Disaster Responses. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 8(4), 489-492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-017-0151-8

Ramos, L. Y. (2014). Estimación del efecto del cambio climático en la precipitación en la costa norte del Perú usando simulaciones de modelos climáticos globales [Bachelor’s tesis, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina,]. https://repositorio.lamolina.edu.pe/handle/UNALM/1899

Rojas, C., Escudero, L., Alburqueque, E., & Xu, H. (2019). Características de El Niño Costero 2017 mediante observación satelital. Boletin Instituto del Mar del Perú, 34(1), 91-104.

Ronchail, J., & Gallaire, R. (2006). ENSO and rainfall along the Zongo valley (Bolivia) from the Altiplano to the Amazon basin. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 26(9), 1223-1236.

Rusticucci, M., & Barrucand, M. (2001). Climatología de temperaturas extremas en la Argentina. Consistencia de datos. Relación entre la temperatura media estacional y la ocurrencia de días extremos. Meteorologica, 26, 69-84.

Siqueira, M., Batista, C., Ambrizzi, T., Drumond, A., & Nunes, N. (2020). South America climate during the 1970–2001 Pacific Decadal Oscillation phases based on different reanalysis datasets. Frontiers in Earth Science, 359. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.00064

Stuart, D., Barber, R., Namias, J., Lagos, P., Wyrtki, K., Rountree, P. R., Parra, S. R., O´Brien, J. J., & Newell, R. (1982). 1982. Prediction of “El Niño” [SCOR Working Group 55]. Scientific Commitee on Oceanic Research. http://www.scor-int.org/SCOR_WGs_Past.htm

Takahashi, K. (2017a). Fenómeno El Niño: Global vs Costero. En K. Morón (Ed.), Avances en la ciencia de El Niño. Colección de Artículos de Divulgación Científica 2017 (p. 52). Instituto Geofísico del Perú.

Takahashi, K. (2017b). Física del Fenómeno El Niño “Costero”. En K. Morón (Ed.), Avances en la ciencia de El Niño. Colección de Artículos de Divulgación Científica 2017 (p. 52). Instituto Geofísico del Perú.

Takahashi, K., & Martínez, A. G. (2019). The very strong coastal El Niño in 1925 in the far-eastern Pacific. Climate Dynamics, 52(12), 7389-7415.

Urbizagastegui Alvarado, R., & Contreras Contreras, F. (2018). Análisis del fenómeno El Niño Costero por el método de las palabras asociadas. Ciência da Informação, 47(3), 117-139.

Vicencio, J., Cortés, C., Campos, D., & Tudela, V. (2017). Enero 2017: Un mes de récords (p. 13) [Informe climático especial]. Dirección meteorológica, secciones de Climatología y Meteorología Agrícola. https://www.opia.cl/601/w3-article-78064.html?_external_redirect=articles-78064_archivo_01.pdf

Vuille, M. (1999). Atmospheric circulation over the Bolivian Altiplano during dry and wet periods and extreme phases of the Southern Oscillation. International Journal of Climatology, 19(14), 1579-1600.

Wanderson, L. S., Nascimento, M. X., & Menezes, W. F. (2015). Atmospheric blocking in the South Atlantic during the summer 2014: A synoptic analysis of the phenomenon. Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, 5(04), 386.

Wooster, W. S., & Guillén, O. (1974). Características de El niño en 1972. Boletin Instituto del Mar del Peru, 3(2), 44-72.